Aging and Hearing Loss I

Many of us know a friend, family member or even a spouse who has experienced greater difficulty hearing as they get older. This is not surprising, because hearing loss in both ears is estimated to affect between 45 and 63% of those over the age of 60 (Lin et al., 2001).

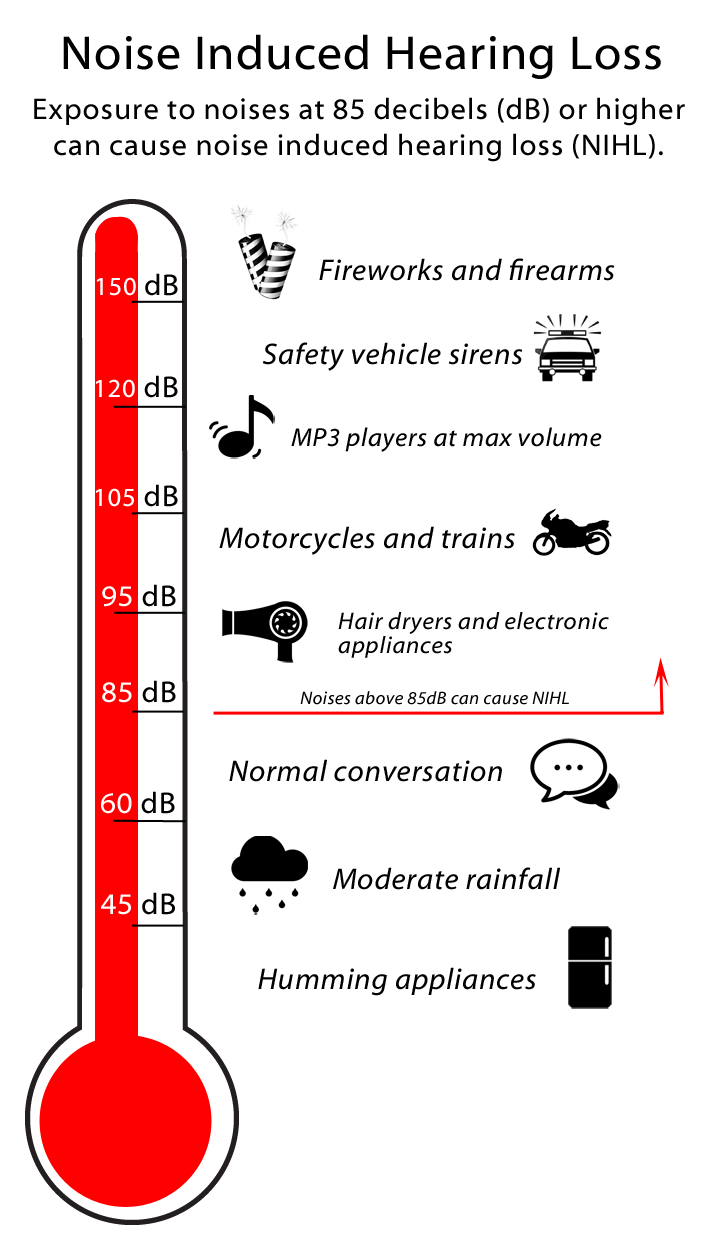

I have discussed several factors that can cause hearing loss in adults, including noise exposure, health conditions, medications and genetics. Now I would like to discuss the changes in our ears and brains as we age.

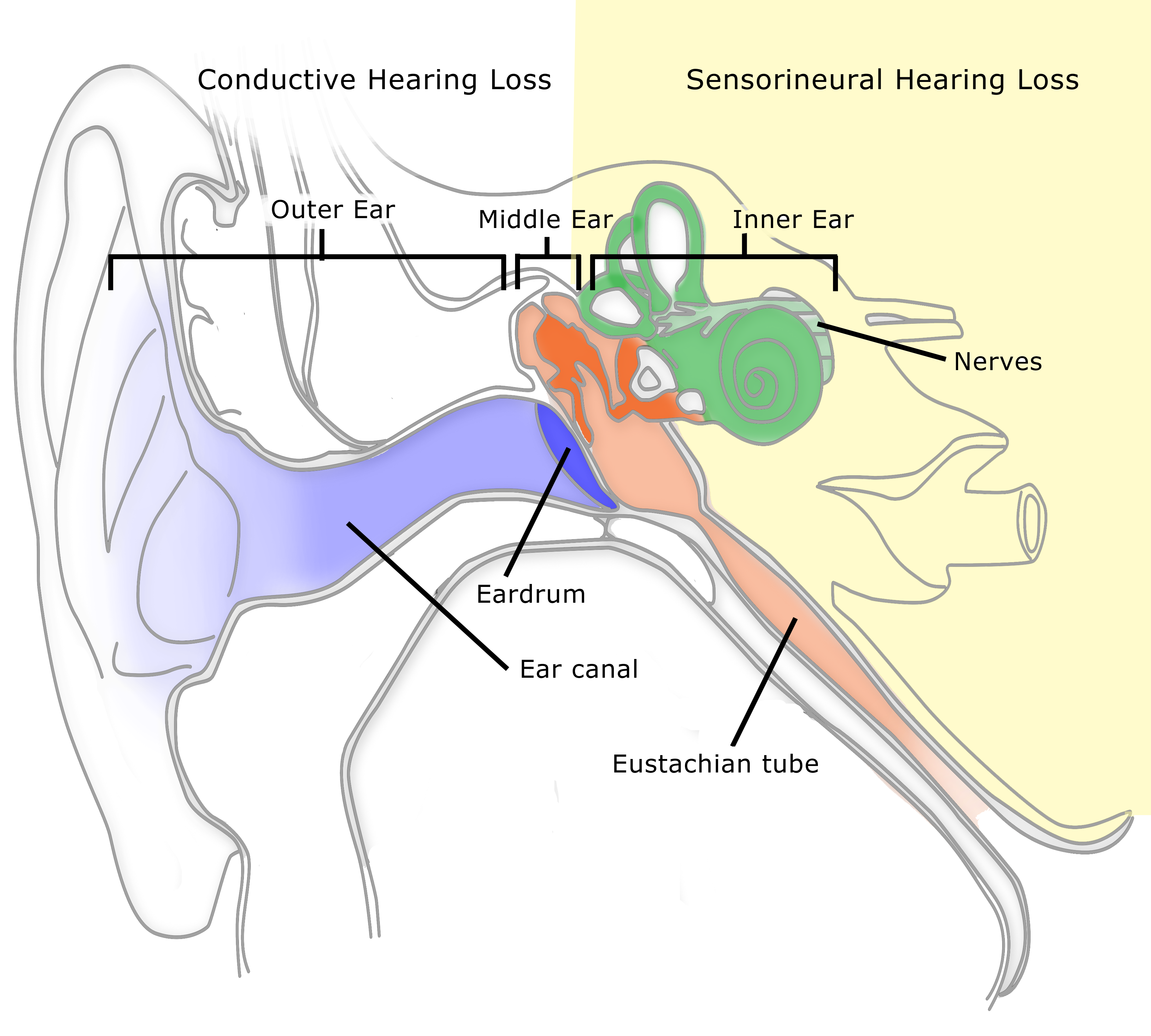

Where do age-related hearing issues affect the auditory system?

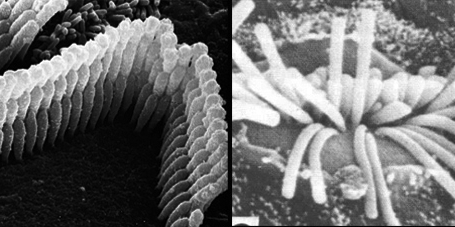

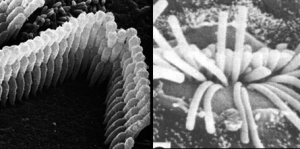

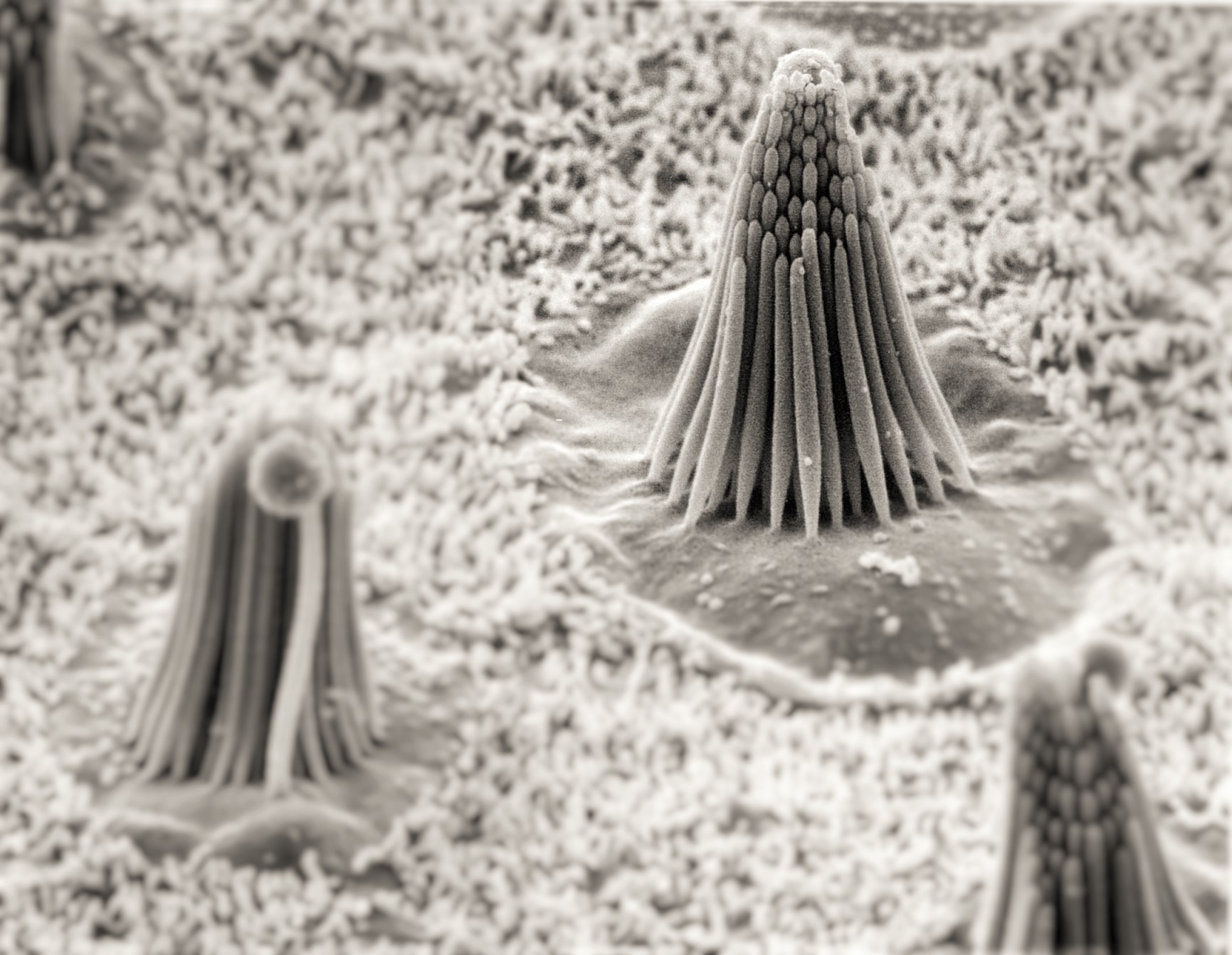

The primary parts of the auditory system affected by age-related hearing loss are the tiny hair cells found in the cochlea (Yamasoba et al., 2013). These cells look like they are standing up in rows when they are healthy, but if they are damaged, they fall over and look more like cooked noodles. These hair cells are a crucial part of the auditory system.

Specific hair cells respond to certain pitches. When those cells are damaged, specific sounds are no longer encoded by the auditory system. A good example of this is difficulty hearing high-pitched sounds as we age. The hair cells that are specifically responsible for encoding high-pitched sounds (e.g., birds singing, female voices, consonant sounds in speech) are functioning improperly, making those sounds difficult to hear.

What does my brain have to do with hearing and aging?

The hair cells found in the inner ear are just the first step in the auditory pathway. Many other nerves and structures found in the brain also enable us to hear. If the hair cells are not functioning properly, adverse chemical and structural changes take place in other parts of the auditory pathway (Mazelová et al., 2002). I think of this almost like a domino effect. When the hair cells in the cochlea are not functioning properly, all the other structures in the auditory pathway are negatively affected in their turn, and the entire system is compromised.

References

Lin, F. R., Thorpe, R., Gordon-Salant, S., et al. (2011). Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 66, 582–590.

Mazelová, J., Popelar, J., & Syka, J. (2003). Auditory function in presbycusis: peripheral vs. central changes. Experimental gerontology, 38(1), 87-94.

Yamasoba, T., Lin, F. R., Someya, S., Kashio, A., Sakamoto, T., & Kondo, K. (2013). Current concepts in age-related hearing loss: epidemiology and mechanistic pathways. Hearing research, 303, 30-38.

Cartoon ©Marty Bucella, jantoo.com. Photos from “Dangerous Decibels”: http://www.dangerousdecibels.org/about-us/the-issues/

Leave a Reply